A Short History of the Acadians and Cajuns

Judy LaBorde

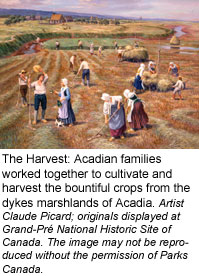

About 400 years ago, a trickle of men and women left their hometowns in France and sailed to Canada where they settled along the eastern coast. They befriended the Indians, devised an ingenious way to drain the salty marshland,s and in time made their tiny settlements into prosperous farms and trading posts. At their peak, they numbered no more than 15,000.

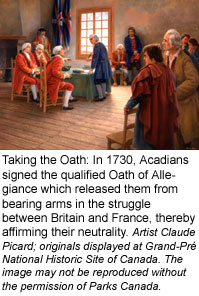

They came to the new world speaking a regional dialect, a patois, which then evolved into an even more distinct dialect known as Acadian, like the people. These little settlements were not terribly important to the King of France. His priority was the Province of Quebec. Neither were the settlements important to the British Crown which instead valued the colonies of New England, to the south of Acadia. And, to tell the truth, the peace-loving Acadians didn't much care for the always-feuding French and British. All they wanted was to be left alone. So, for about 150 years, the Acadians became very adept at neutrality. They promised not to take sides or engage in warfare. And, they kept their word.

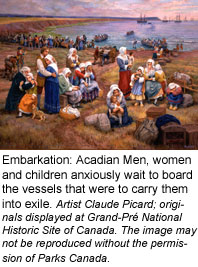

All that came to a brutal end in 1754, when Major Charles Lawrence illegally demanded that the Acadians sign a loyalty oath to the English King and repudiate their Catholic religion. (Lawrence did not have the approval of the British government to do this.) When the Acadians refused, the men were forced from their families and arrested. Within days, all the farms, barns, churches and shops that made up the Acadian colonies were burned to a crisp. So were their crops and livestock. A mass expulsion ensued.

Amid total chaos, families were separated and forced onto hastily assembled ships. What followed were years and years of aimless wandering. Some Acadians landed in England and were promptly arrested. Some went to France and were treated as outcasts. Others arrived helter skelter at ports in Maine, Connecticut, and other New England colonies. In the Carolina colonies, attempts were made to take children from their parents and force them to work on the plantations. Others were sent to Haiti, Newfoundland, Argentina and Uruguay. The Acadians were a people without a country, a people who could rely only on each other for survival.

In 1764, one of the ships arrived in Louisiana, which at that time was a colony ruled by Spain. The Spanish Governor, Galvez, did not know they were coming but could see an advantage to their presence as a counter influence to the British settlements nearby. Over the next 20 years about 3,000 Acadians found their way to Louisiana. They settled the mosquito-infested swamps, bayous, and prairies that nobody wanted. They did the back-breaking jobs that others would not do. With their strange sounding dialect, they were even rejected by other Frenchmen already in Louisiana. Poor and illiterate, with a language, culture and customs that set them apart, the Acadians had only each other. When it was time to marry, they married their own. Otherwise, who knows if they would have made it.

This pattern continued until the aftermath of the Civil War, which devastated the economy and social structure of the South. With poverty so widespread, what difference did it make that the Acadians were poor. If anything, they had already proven their capacity to survive a hostile world with close community and family ties. Gradually, Acadians began to marry non-Acadians. The new spouses often learned to speak French and were absorbed into the population that came to be known as "Cajun." This explains why some of Louisiana's best loved Cajun musicians have non-French names like McGee, Toups, Riley, and Abshire.

The next big change occurred because of World War II. Returning veterans had experienced a much larger world which whetted their appetites for a good education, better-paying job, a nice home. This caused a gradual migration away from small, exclusively French-speaking communities into a more modern, mainstream world.

The result of these and other factors (such as the practice of punishing children who spoke French on school grounds) was the gradual, but not total, Americanization of the Acadians. The practice of marrying non-Acadians continued, and the term "Cajun" is used to describe the culture that evolved from the Acadians.

The irony about the Cajuns in America today is that despite efforts over the last 250 years to destroy their culture, they have indeed survived as a distinct group. While other ethnic groups dissolved into the proverbial melting pot, the Cajun way of life -- spicy food, lively music, family traditions -- is known and beloved the world over.